For decades Ireland has been flying high as the undisputed global leader in aircraft financing and leasing thanks to a long history in the industry and the republic’s corporate culture, but does a global tax reform deal currently afoot threaten to bring it down to earth? Alejandro Gonzalez considers the prospects for tax change.

Ireland has been at the centre of the global aircraft leasing industry for nearly half a century. The story begins with Ryanair’s Tony Ryan, who as an Aer Lingus manager in the early 1970s started out subleasing two company planes before setting up his own company, GPA (Guinness Peat Aviation) operating out of Shannon Airport.

Access deeper industry intelligence

Experience unmatched clarity with a single platform that combines unique data, AI, and human expertise.

Ryan’s business plan was simple, offer aircraft leasing as a way of opening up aviation to second-tier airlines who would struggle to get a look-in in an otherwise prohibitively expensive industry.

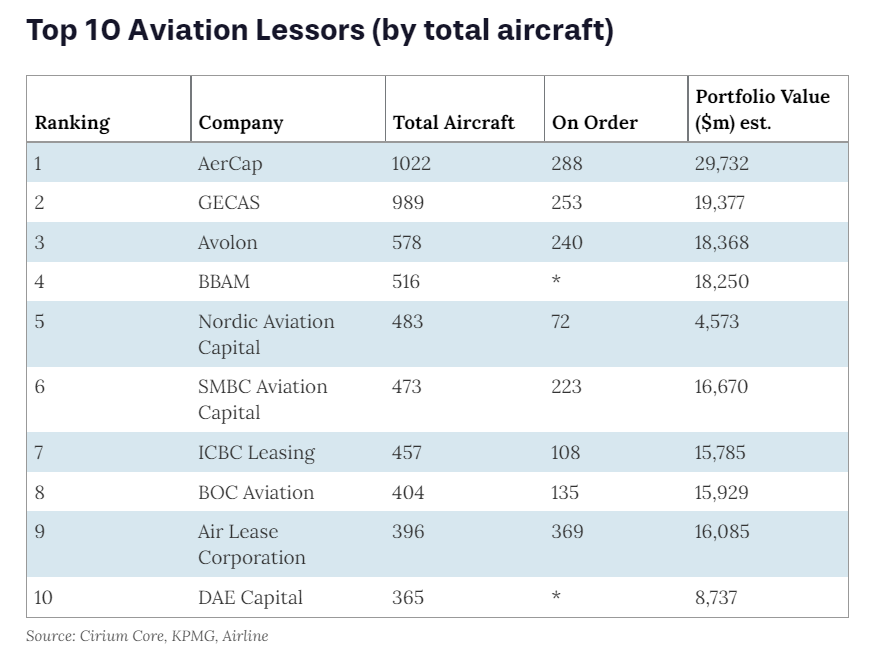

Today, over 50 aircraft leasing companies are based in Ireland (including 14 of the world’s top 15 aviation lessors), and Ireland has a 65 per cent share of the global leasing market, according to PwC.

Aircraft Leasing Ireland (ALI), a trade body for the sector with 32 members, says the industry employs around 5,000 people and contributes €550m a year to the Irish economy.

So, what’s the secret to Ireland’s success in attracting aviation leasing companies?

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataPart of the answer is its history as an early mover in this field, it has attracted professionals with top experience, it has strong supporting legal services and technological infrastructure, is host to an English-speaking community and, as an EU member, doing business in Ireland offers unfettered access to its 27-member states.

David Berkery, Partner Aviation & Transport Finance at the law firm A&L Goodbody believes that Ireland’s low corporate tax rate as well as the broader eco-system beyond tax which makes Ireland so attractive for aircraft lessors. “The industry-specific, professional supports available; the experienced workforce in situ; the educational initiatives on offer (from certificates to diploma courses to Masters degrees) and our history as pioneers in aviation leasing, would all be impossible to replicate anywhere else. There’s a real sense that aircraft leasing is ‘in our blood’,” he says about the favourable local conditions.

Ireland’s corporate tax

Clearly, aircraft lessors have also been attracted to Ireland’s 12.5 per cent corporate tax rate on trading profits, which remains attractive despite growing competition from other aviation hubs in Hong Kong, Singapore, Labuan (Malaysia), Malta, Cyprus, and the China Free-Trade Zones.

“Ireland has long competed with aircraft leasing hubs offering even lower or no corporate tax but our greater tax advantage is that we enjoy an extensive double-taxation treaty network thanks to the efforts of successive Irish governments in reaching these bilateral agreements with multiple countries over the past 40 years,” says Berkery.

With respect to aircraft investments, rental payments can typically attract high levels of domestic income tax, so Ireland’s network of double taxation treaties (74 countries to date) help protect corporations against the risk of excessive foreign taxation on rental payments on aircraft. Calculations by PwC suggest almost 80 per cent of Ireland’s double tax treaties deliver a favourable result for aviation finance companies.

G7 corporate tax proposals

G7 corporate tax proposals

Against this backdrop, the G7’s commitment in early June to a global minimum corporate tax of at least 15 per cent poses a threat to nations such as Ireland that rely significantly on corporate tax cuts to sustain their attractiveness for investors.

Under the commitments – backed by about 130 countries, representing 90 per cent of the world’s GDP – profit will be based on a corporation’s place of sale and not its place of residence.

Not included in the list of backers is Ireland, one of only nine countries to reject a draft agreement on international corporate tax reform at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), championed by President Biden.

Despite Ireland’s opposition to the OECD proposal, there has been speculation about whether the Emerald Isle might be prepared to relinquish its 12.5 per cent tax rate to avoid reputational damage.

But Paschal Donohoe, Ireland’s finance minister, has dispelled these suggestions – for the time being – telling the Irish national broadcaster RTE on 15 July that the country’s corporate tax rate “has been a key feature of our economic policy now for decades” and he was “committed” to maintaining that.

Significantly, however, Donohoe did not rule out a change to its tax regime, saying he was in the middle of negotiations and was pushing for Ireland to retain its low rate. He said: “I think it’s very reasonable for me to say that if there is an agreement that I believe is in our national interest to be part of, I would recommend that to the government.”

Donohoe added that the OECD agreement, as it stood, did not have the detail Ireland needed: “Whether we’re in the final agreement or not will depend on the detail”.

Even if Ireland does ultimately commit to the agreement, by winning OECD concessions, Sebastian Shehadi, political editor at our sister publication Investment Monitor, says that getting a global deal through could take a decade. He writes: “Simply put, Biden is all carrots and no sticks at the moment, and it will take huge carrots to convince the likes of Ireland. Sticks, therefore, will be needed.