The Bank of England’s Term Funding Scheme for SMEs will afford big banks with cheap financing, but how will these funding benefits be passed on to non-bank lenders? Alejandro Gonzalez reports.

One of Mark Carney’s last acts as governor of the Bank of England (BoE) in March was to shower the economy with a once-in-a-generation stimulus package.

To offer perspective, the Office for Budget Responsibility, the UK’s official budget forecaster, said the amount the government will have to borrow to pay for this (around 27% of GDP) is comparable with the total government borrowing after six years at war following WWII.

To get through the 2020 pandemic, the Conservative government and the central bank have announced £330bn-worth of government-backed loans, grants and tax cuts to date for struggling companies and individuals.

One tranche of this package is a Term Funding Scheme (TFS) for businesses, announced in mid-March. The Bank of England stating that it “offers additional incentives for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (TFSME), financed by the issuance of central bank reserves.”

With about 60% of all UK leasing by value done with SMEs, the Finance & Leasing Association (FLA), is lobbying hard to convince policymakers to make sure specialist finance and leasing companies are on the receiving end of its funding initiatives, such as the TFS.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataVying for a piece of the action are specialist non-bank financing companies, which have blossomed since the 2008 financial crisis and who now make up over 50% of the FLA’s membership.

The ascendency of specialist lenders was assured when high street banks became more risk-averse and turned their backs on SME lending. These companies established their foothold through a network of hundreds of brokers, niche operations and by increasingly offering their financing through fintech businesses.

Today, with Covid-19 threatening the livelihoods of non-bank customers (and non-bank lenders themselves), questions remain about how providers of asset finance to SMEs will fare from the upheaval to credit provision in the UK.

Credit crunch and 2012

The TFSME had its origins in the Funding for Lending Scheme (FLS) of July 2012, launched four years after the onset of the financial crisis of 2008.

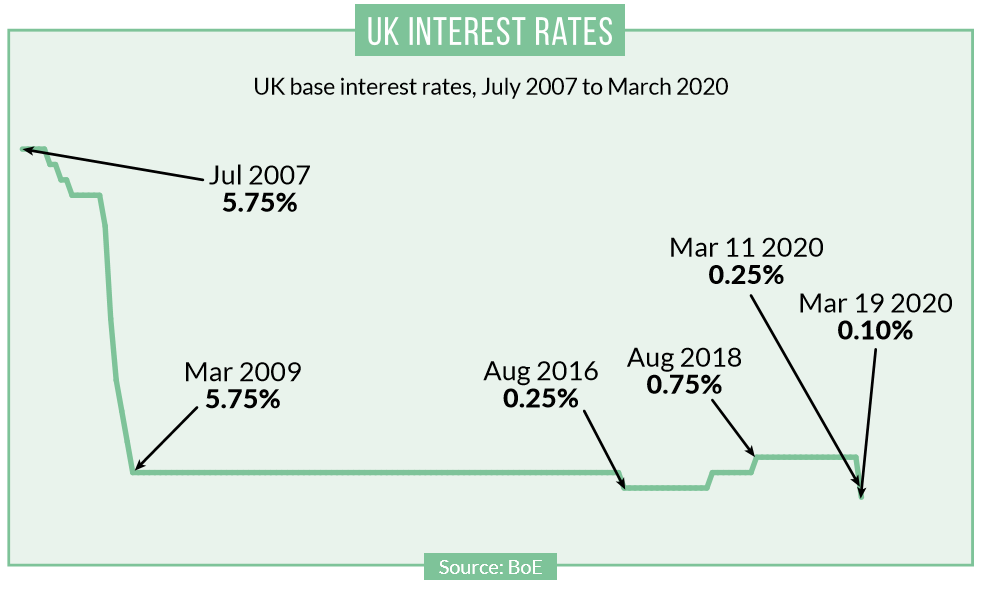

A cut to interest rates (to 0.5%) and quantitative easing (worth £375bn) had failed to lift productivity or increase bank lending, landing the UK in a ‘liquidity trap’, a ‘rare’ event at the time (but all too familiar now), that occurs when monetary policy loses all effectiveness to sway events and looser policy does nothing to encourage spending.

The US, the Eurozone and the UK banks were all similarly affected. Risk-aversion was the order of the day and low-interest rates were squeezing bank profits and discouraging any new lending.

In the SME sector, businesses were struggling to obtain finance with many dealing with the withdrawal of promised finance and increased costs of borrowing and financing.

The FLS entered the fray when traditional policies had failed to kick-start bank lending at a time of rock-bottom interest rates. Originally unleashed to lift mortgage lending, it was later narrowed to only include SME lending.

In describing how the FLS works, the BoE says: “Specifically, banks and building societies are offered funding with both the amount and its price depending on the amount they lend.”

By November 2015, the FLS had provided £60bn to banks to support households and businesses, the Financial Times reported at the time.

The scheme’s managers – perhaps seeing an end to the crisis in sight – said it would be slowly phased out and expire in January 2018.

Brexit 2016

Brexit 2016

Following the vote to leave the EU in June 2016, the UK entered a renewed period of economic uncertainty, with growth at its weakest rate since the global financial crisis almost a decade earlier.

As growth forecasts dipped relative to pre-referendum levels and the demand for finance showed signs of weakening, the nation’s macroeconomic managers rolled out a series of measures designed to mitigate the impact of the Brexit vote.

To manage the uncertainty – expected to last until after the withdrawal bill, then about four or five years away – the Bank of England and HM Treasury rolled out three monetary policy measures in August 2016.

The first, an interest rate cut (to 0.25%), the second, the expansion of asset purchases (of £70bn), and third, the unveiling of a TFS.

Like the FLS before it, the lowering of interest rates had squeezed the profitability of banks and finance companies, and so TFS served as the go-to solution to take the pressure off lenders’ margins.

According to an FT report at the time, based on estimates by analysts at Citi, each rate cut of 25 basis points had the effect of reducing large-cap domestic UK bank earnings by approximately 2% to 3%.

Under the 2016 scheme, banks were offered a generous rate, close to the lower bank rate, for four years. The offering was structured with a series of incentives to encourage banks and building societies to pass on the rate cut to households and companies.

In a review of the scheme, the BoE said: “The design of the Scheme reflected this primary objective and it was calibrated so that the reduction in Bank Rate could have a broadly neutral impact on lenders’ margins in aggregate.”

When the scheme closed to new lending in February 2018, it had made £127bn in loans.

Looking back two years after the scheme was launched, the BoE said: “Observations from the period after the TFS was launched suggest that the reduction in Bank Rate was passed through to lower lending rates on loans such as mortgages, without any significant compression in lenders’ net interest margins, or in the supply of credit to the economy.”

Coronavirus 2020

Fast forward to the current situation and economic shock caused by Covid-19, which could hardly have come at a worse time for the UK, in the midst of its Brexit negotiations with the EU and the ongoing economic uncertainty that it brought about.

Now crippled by a virtual global shutdown in business, the IMF and the Office for Budget Responsibility, the UK’s fiscal watchdog, have forecast that the UK faces the deepest recession since the 1920s.

Not for the first time, in the frontline of this latest economic crisis are SMEs, which the government has described as ‘the backbone of the British economy’.

According to the ONS, the number of businesses in the UK at the start of 2019 was 5.9 million (up from 3.5 million in 2000), a rise of 68%, which may also explain the rise in appetite for financing from non-bank asset finance providers.

With the economy now quarantined, government commitments of state aid would keep SMEs from going under.

SME funding

The British Business Bank (BBB), a government-owned development bank (itself a child of 2008), would funnel term loans, overdrafts, invoice finance and asset finance to SMEs.

Under instruction from the chancellor of the exchequer, Rishi Sunak, the BBB was tasked with administering two complementary schemes.

CBILS, for SMEs with a turnover below £45m and CLBILS, for larger SMEs with a turnover above £45m.

In both instances, the lending amounts were commensurate with the size of the business alongside commitments by the government to support lenders with 80% guarantee on loans.

Unlike the CBILS scheme for smaller companies, the CLBILS loans will carry an interest rate decided by banks.

According to the FT, about 10,000 companies may fall within the CLBILS group, including many listed companies in the FTSE 250 that cannot get an investment-grade rating to access the Bank of England’s commercial paper (bond) scheme (the Covid Corporate Financing Facility).

Industry concerns

A number of concerns have been raised about the schemes. One involves the terms under which the funds are being offered, the other the slow speed at which money has been reaching SMEs, particularly small and micro-businesses.

The BBB’s precursor to CBILS, the Enterprise Finance Guarantee (EFG) had achieved approximately £50m a quarter in funding in 2019, so expectations that it could leap into action and upscale to manage its portion of a £330bn rescue plan were not high among some observers.

Striking a different note, Julian Rose of Asset Finance Policy said about CBILS in a blog posting: “It is an important tool in government support for SME lending, but it doesn’t transfer enough risk to government to persuade lenders to set aside their usual due diligence requirements.

“Perhaps the EFG should never have been renamed as a Business Interruption Loan Scheme. Changes, such as making the loan interest-free for an initial period, cannot transform a shared risk scheme for marginal business loans into something far wider.”

Others were concerned about the red tape that a central government scheme would attract. At the scheme’s outset, there were over 40 approved lenders on the BBB lending panel, made up of high street banks, challengers and non-bank lenders. For some observers, the BBB’s accreditation processes were too cumbersome and bureaucratic for the emergency at hand.

Since CBILS was launched (on 23 March) the total value of loans approved has been low.

A recent survey (15 April) of 701 SMEs by the British Chambers of Commerce found that just 2% of respondents had achieved payouts from the CBILS scheme.

Approximately £2.8bn has been handed out to SMEs via CBILS by 23 April, according to UK Finance, the trade body for banks and finance companies.

While much of the CBILS heavy lifting has fallen on the shoulders of too few lenders, with The Sunday Times reporting (on 19 April) that despite more than 40 accredited lenders offering loans under the BBB scheme, the bulk of the lending is being done by just two banks.

The government-owned NatWest had approved 5,001 loans (worth £840m), while HSBC had approved 2,026 loans (worth £278m). Other high street lenders Barclays, Lloyds and Santander declined to provide lending statistics, raising concerns that some lenders are not pulling their weight.

A bias against small borrowers was picked up by MPs during a Treasury Select Committee, which was taking evidence via videoconference in mid-April as part of its inquiry into the economic impact of the coronavirus emergency on businesses and individuals.

The committee heard about an ‘eligibility gap’ for the government’s various business bailout schemes and that the biggest delays were being experienced by companies applying for loans of less than £25,000.

Calls to extend 100% loan guarantees to smaller borrowers came from the SME representative body, the Federation of Small Businesses, and increasingly elsewhere.

On 17 April, Andrew Bailey, the governor of the Bank of England, suggested that SMEs might need grants rather than loans to keep them afloat in the current circumstances, but he stressed this was a decision for the government.

This point was reiterated on 20 April by Andy Haldane, the chief economist of the BoE, who said that underwriting 100% of lending to the smallest of firms had worked in other countries such as Germany, though it was ultimately a political decision.

On 21 April, Chancellor Sunak said he was looking at ways to improve the process and “strip out bureaucracy”, but dismissed calls to increase the guarantee on the loans to 100%.

“I’m not persuaded that moving to a 100 per cent guarantee is the right thing to do,” Sunak said.

As this article goes to press, there are reports that Sunak is “weighing-up” whether to back 100% loans of up to £25,000 to micro-SMEs.

Given the role that non-banks play in funding smaller SMEs, the FLA’s backing for 100% loan guarantees for micro and small businesses lending has so far been oddly absent.

Term Funding 2020

Julian Rose believes TFS may offer an SME funding option that assimilates non-bank lenders, once the lockdown begins the process of unwinding, something he says has received relatively little attention in the financial press.

In keeping with its earlier appearances, TFS was timed to offset the squeeze on commercial banks’ net interest margins triggered by a cut in the base rate. On 11 March the base rate dropped to 0.25% and, eight days later it sank to the historic low of 0.1%, where it currently sits.

The basis of the scheme, according to White & Case LLP, is to ensure the benefits of the rate cut are passed on to the real economy and to “incentivise additional lending to businesses, and the additional incentives for lending to SMEs should assist those companies that typically suffer the most during periods of heightened risk aversion and economic downturns.”

As SMEs emerge from coronavirus hibernation and look to invest and trade in the recovery phase of the crisis, they will likely (in the absence of cash funding) turn to asset finance, says Rose.

“At first look, the TFSME might not look so interesting. It doesn’t provide any lending risk support to lenders and only certain banks can apply (although others can be expedited through the qualification process),” he adds.

TFS comes with other benefits: a) cheap four-year funding for banks (at, or close, to base rate); b) incentives to encourage SME lending, and; c) the “ability to use asset finance as eligible collateral, with clear qualification criteria,” he says.

What’s more, Rose says: “the low funding cost without a cap on lending rate provides some degree of cover for extra uncertainty.”

Non-banks

The FLA, no doubt swayed by the sizeable representation of its non-bank members, and the proportion of FLA member new business generated by its non-bank members (33% in 2019), took a different tack.

While recognising the government’s existing support schemes are “helpful”, it says these schemes are presently “unsuitable” for managing the “unprecedented demands for forbearance” from FLA members’ customers.

What the chancellor’s schemes need to work efficiently are “modification or enhancements to help specialist non-bank funders,” the FLA noted in a briefing paper.

The FLA’s concern is that Term Funding leaves specialist non-bank providers out in the cold and dependent on seeking credit from authorised banks to access BoE funds, so it wants to cut out the middleman.

In a blog, Stephen Haddrill, the director-general of the FLA, said the danger of excluding non-bank lenders from distributing funds directly was the BoE would fail to “get funding to as many SMEs as possible.”

Putting his case in a letter to the editor of the FT in mid-March, Haddrill said: “Asset finance (leasing and hire purchase) is the second most popular type of funding for SMEs, and worth £20bn of new finance a year. These firms are here and ready to help.”

FLA’s rapid access

The FLA’s government proposal is for a “Rapid Access Term Funding-like Scheme for non-bank funders,” administered through the BBB.

Such a proposal would require funder eligibility to be streamlined. “If the funder is FCA [Financial Conduct Authority] regulated or already part of the BBB scheme, then it would automatically be able to access the funding,” the FLA says.

Should the FLA get its way, non-banks may be entitled to the full benefits of SME lending under the scheme.

While Rose agrees that direct funding for non-banks is the ideal solution, he points out that under the existing BoE scheme rules there’s an indirect route that allows participating banks to distribute funding to SMEs through non-banks.

“It’s far from ideal”, says Rose, “but could be worth firms considering in order to help overcome capital constraints that seem likely to occur during the recovery phase.”

“Lending to non-bank financial institutions is possible, but this would not qualify as SME lending, so the incentives to lend are less favourable,” he says.

A way forward, in the meantime, is for the incentive regime to be reconfigured, “so that lending that is clearly being passed through to SMEs is treated as SME lending.”

But to find a solution agreeable to the parties concerned will require trust, among other things, which was sadly lacking in the aftermath of 2008.

“The problem then was that those responsible for the [FLS] Scheme in the participating banks weren’t familiar with the structure of the asset finance market. By the time the right discussions started, the need had largely gone away,” Rose recalls.

Clearly, today’s circumstances are vastly different. The bank rate cut is as low as it’s ever been, bank profits are squeezed ever more and non-bank customers are quickly running out of time.

Arriving at a compromise will be made all the harder via Zoom conference calls.

It’s not all doom and gloom though. The current landscape has plenty of positives, after 2008 the commercial banks have bigger capital buffers and, says Rose, banks have become more used to working with asset finance companies, including the many fintechs offering asset finance.

What is needed is “collaboration and innovation,” says Rose, and recognising each another’s strengths and weaknesses will be critical to the job of distributing TFSME funds to SMEs when the dust settles on Covid-19 and Britain looks to start picking up the pieces.