With global airlines in free fall, the demand for financing is expected to increase, benefiting aviation finance companies who specialise in sale-leaseback, Alejandro Gonzalez reports

-O-

Losses in the airline industry globally are expected to rise to an estimated $314bn (£253bn), according to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), due to a 55% fall in passenger revenue this year compared to 2019. This is 25% more than the aviation body previously forecast at the end of last month.

The industry works on notoriously thin margins and although it has survived downturns over the past couple of decades – taking hits over 9/11 in 2001, SARS in 2002-3, and the 2008 credit crunch for example – none of those events compare with the current crisis.

IATA’s director-general, Alexandre de Juniac, told the international press on 14 April: “The industry’s outlook grows darker by the day. The scale of the crisis makes a sharp V-shaped recovery unlikely. Realistically, it will be a U-shaped recovery with domestic travel coming back faster than the international market.”

So, where does this leave aviation lessors?

Aircraft financing is a billion-dollar industry, valued at $126bn in 2018 globally. Pre Covid-19, this figure had been expected to rise to $181bn by 2023, according to Boeing.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataBut, as largely grounded airlines can bring in very little revenue and have started eating through their cash reserves, the only thing keeping them afloat is their ability to pay their debts and manage their other outgoings.

Given this context, it’s not surprising that IATA has estimated that airlines around the world will burn through $61bn during the second quarter (ending 30 June) alone.

In the absence of a government bailout, as is the case in the UK, airline management boards are tasked with having to raise funds from other investors and/or negotiate better terms from their lenders, landlords and aircraft lessors.

Financial restructuring is one course of action that many in the industry will be looking at to stay in the air. Leasing is an attractive option for airlines, with sale-leaseback funding central to capital raising in aviation.

Aviation finance expert, Justin Benson, who leads the global asset finance practice at White & Case LLP and has over 25 years’ experience in the industry, believes that the sector’s funding diversity is one of its strengths and may explain the aviation industry’s resilience and longevity to date.

Commercial bank lending, the capital markets, export credit agency (ECA) support, and commercial insurance-backed financing have all been used as financing options, but operating leasing and sale-leasebacks were probably the most common staple diet for most airlines in this sector before the Covid-19 crisis took effect, says Benson.

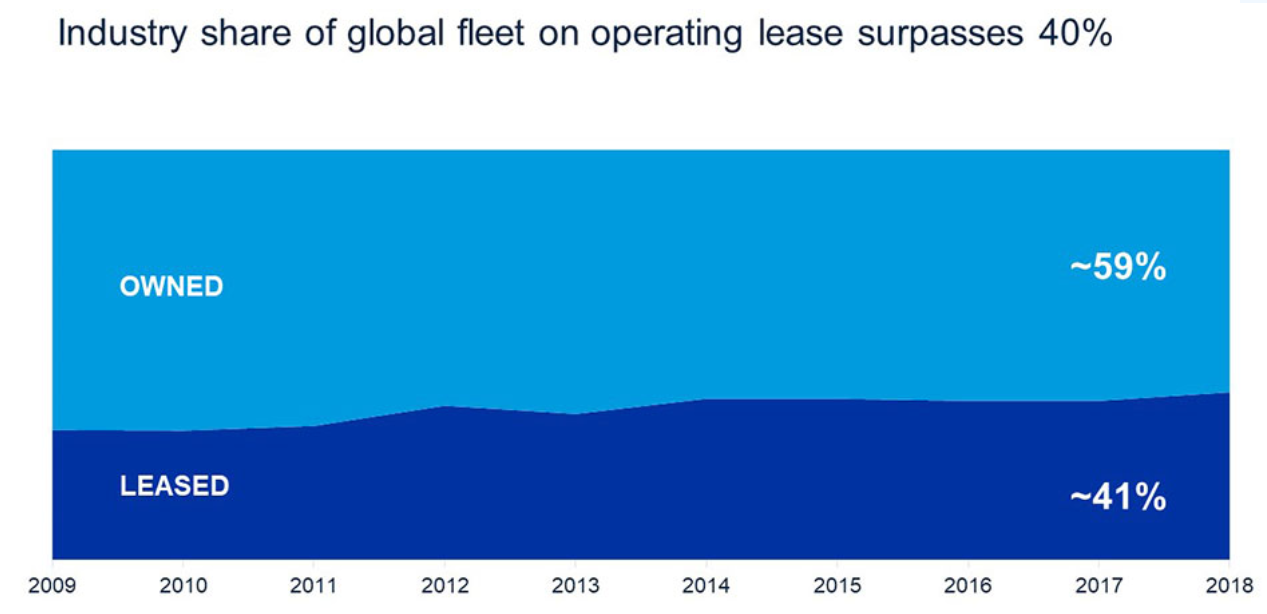

“In recent years, leasing has accounted for 45% to 50% of the aviation financing market,” he adds.

His assessment is mirrored in Boeing’s 2019 Current Aircraft Finance Market Outlook (CAFMO) report, which found that 50% of Boeing’s deliveries involving lessors were for sale-leaseback transactions.

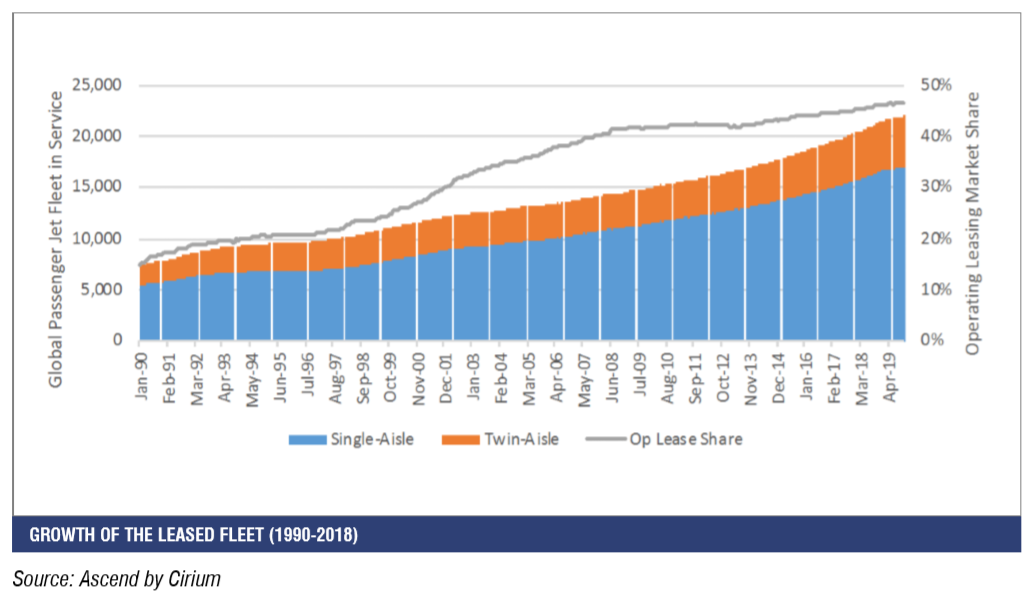

According to the CAFMO report, leasing has experienced a boom in the last couple of decades.

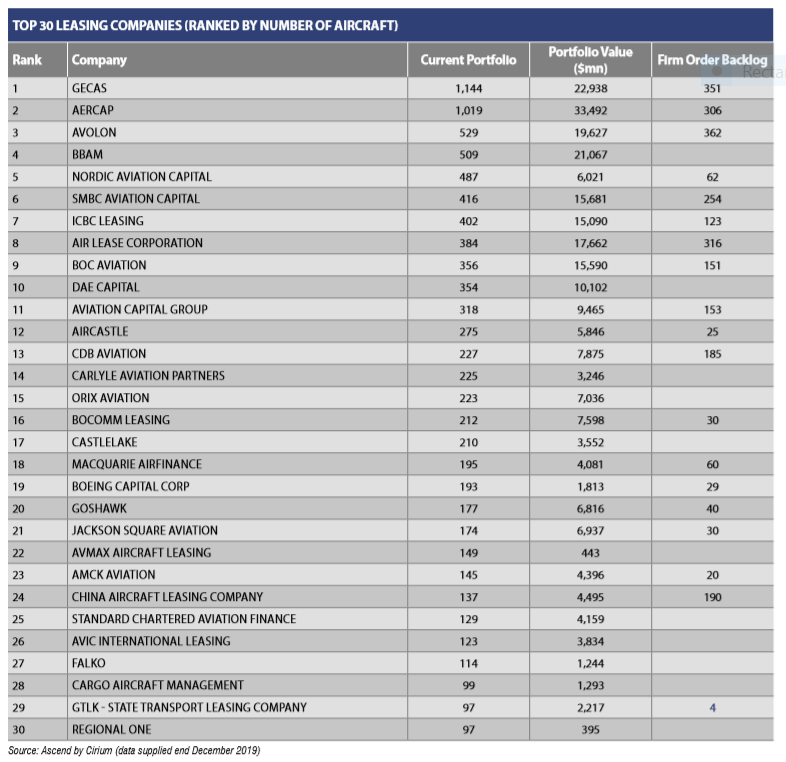

In 2002, there were fewer than 100 leasing companies, with the top two lessors maintaining more than 40% market share (by aircraft). In 2019 there are more than 150, with the top two lessors accounting for approximately 20% of the market, according to the report.

The benefits that leasing brings are clear, says Benson.

Even in far less challenging times, leasing doesn’t tie-up an aircraft operator’s much-needed capital, it can allow the business to manage decreases and increases in capacity as needed and sale/leasebacks can realise a profit for airlines.

“We’ve advised clients during times of huge sector upheaval, including 9/11, the 2008 financial crisis, and the virus outbreaks of SARS and MERS,” says Benson.

Like Covid-19, the economic effects of SARS and MERS were immediately felt by an aviation sector “used to weathering storms,” says Benson.

Despite the hard times, the aviation sector was eventually buoyed by the demand for air travel and Benson believes the same will happen after the threat of Covid-19 has passed.

He says that the industry, which is correlated to GDP growth, will recover as the world economy gets back on its feet. In its April World Economic Outlook, the IMF says it expects the global economy to contract by about 3% in 2020.

“Assuming the pandemic fades in the second half of 2020 and that policy actions taken around the world are effective in preventing widespread firm bankruptcies, extended job losses, and system-wide financial strains, we project global growth in 2021 to rebound to 5.8%,” the IMF reports.

Benson commissioned White & Case’s first aviation finance sector survey, entitled Navigating Turbulence, in Q4 2019. The report collates the views of 100 C-suite executives who had either financed or invested in aviation in the last three years.

The idea of the survey was to get a global snapshot of the industry and to understand the regional nuances, says Benson.

One of the survey’s major findings was that the Asia-Pacific region stood out as the standard-bearer of growth – against a slightly less promising outlook for North America, Europe, the Middle East and Africa – and that’s before the effects of the government-imposed lockdowns were felt globally.

Certainly, all eyes will be on the Asia-Pacific region as lockdown restrictions begin to lift there first, although it remains to be seen whether the positive expectations of investment levels in the region’s aviation sector will play out quite as rapidly as predicted by the survey.

In recent months, airlines have adopted a number of measures to stay afloat, but the depth of the Covid-19 crisis has suggested to many observers that the sector is entering a phase that will see weaker airlines collapse and consolidation is expected to accelerate, especially across Europe.

If this is true, as airline bankruptcies rise and defaults beckon the demand for financial restructuring will increase.

In March, Rishi Sunak, the chancellor of the exchequer, declined to offer an industry-wide bailout to airlines and urged companies to explore options to improve their cash holdings.

In a statement, Sunak told the sector that: “Taxpayer support would only be possible if all commercial avenues have been fully explored, including raising further capital from existing investors”.

Unlike the US, France and Germany which quickly moved to offer financial support to their respective national carriers, Britain’s Conservative government took a hard line to requests for state assistance due to the complex ownership arrangements of the UK aviation sector.

Andrew Lobbenberg, an aviation analyst at HSBC, told the Financial Times: “If you look at UK airlines and airports they’re not all UK-controlled.

“British Airways is owned by International Airlines Group, which is a Spanish company, and the largest single shareholder is Qatar Airways. Virgin is 49 per cent owned by Delta Air Lines of the US.”

Meanwhile, Wizz UK, Norwegian UK and Ryanair UK are subsidiaries of parent airlines from Hungary, Norway and Ireland, respectively.

“The deployment of taxpayers’ money into aviation becomes complex when you recognise the non-UK shareholders behind the businesses”, Lobbenberg told the FT.

This leaves the UK-based airlines doing what they can to conserve and raise cash. This has involved cutting labour costs by reducing working hours or offering staff unpaid leave, grounding routes and running smaller aircraft.

It has also involved companies seeking holidays from aircraft lease payments and raising cash by selling and leasing back fleets.

This has strengthened the hand of lessors who will look to do deals with underleveraged companies who own most of their fleet outright and may be disposed to a sale-leaseback arrangement, in exchange for cash.

In a recent briefing, Benson’s team identified several potential opportunities for the aviation financing market, one of which involves lessors entertaining joint ventures.

With UK-based airlines keen to show the chancellor they are doing everything possible to raise capital before asking for state aid, lessors are in a position to add more aircraft to their portfolios at a good price. But with the prospect of loan impairments on the rise, the risk for lessors is also significantly high.

Fortunately for leasing companies, hedge funds and private equity investors may feel tempted to enter the sale-leaseback space, making the idea of joint ventures attractive to lessors.

Benson has noticed interest picking up among some White & Case clients for “side-car deals”, arrangements that bring together the expertise of lessors who understand the market and deep-pocket investors who are looking for new areas in which to invest cash and generate returns.

While the effects of the pandemic may be with us for some time, the fundamentals of aviation financing have not changed. Unlike other less mobile high-value assets, aircraft are by their very nature transportable and can be moved to where their value can be best put to use, making them highly liquid as an asset class, which investors and lessors like, says Benson.

So, as the global economy enters a downturn, the aviation industry looks set for a bumpy ride, characterised by weak demand, rising bankruptcies, an absence of liquidity, low oil prices, ultra-cheap central bank money and historic levels of fiscal stimulus.

In this context, leasing companies look set to reap the rewards from the demand for leasing finance and the affordability of credit.

However, the drying up of liquidity cuts both ways.

Lessors who have borrowed too much, operate unsustainable business plans or who possess too few reserves, may find they can no longer compete in a crowded space.

Aviation finance companies with scale, able to access the cheapest funding and who specialise in sale-leaseback deals may be best-placed to fly high.